I first read Godchild when I was probably too young to read Godchild. It's not that I think the series was too violent or explicit for a 10-year old, more that I think I missed a lot of the plot and subtleties by reading it when my brain was still mushy. How did I just now realize that Dr. Disraeli was a hermaphrodite implanted with his sisters' organs?! That seems like a huge thing to miss!

Feeling nostalgic a decade and some change later, I decided to track down and re-read the entire series for nostalgia's sake — including all 4 (previously unread) books of the prequel series, The Cain Saga.

This will almost certainly contain spoilers, though I don't think anything I've written detracts from any of the twists or the plot itself. This said, if you haven't read one or the other (or both) and want to avoid (fairly vague) spoilers, this is your warning!

I always knew that Godchild was a sequel/continuation, but I wasn't sure how much that affected it as a stand-alone series. Originally written in 1992, The Cain Saga encompasses four books split across five English-language bound volumes: Forgotten Juliet, The Sound of a Boy Hatching, Kafka, and The Seal of the Red Ram, which is a two-parter. As someone who read Godchild first, as it was more easily accessible, I was always sure I was missing something crucial by not having read The Cain Saga. I was very excited to find all five volumes on Thriftbooks (not sponsored, I just genuinely use them) and while I think it makes for a fantastic prequel, I learned that you really don't need to read it in order to enjoy Godchild.

This is not me saying that any of it is bad. I'm a huge fan of Kaori Yuki's work, and if anything, I think the fact that you don't need to read The Cain Saga to fully appreciate Godchild is a testament to how well the sequel series is written. If you read Godchild first, however, you might be a little thrown off for the following reasons:

1. Lack of character growth

I was expecting The Cain Saga to reveal hidden depths previously unknown to us, to better set up character relationships, or to add context to characters that might have been useful when reading Godchild. In this sense, it fell a little short; Cain's father still despises him just for existing, Cain's half-brother still wants his eyeballs, and Cain is still... Cain. Though I do think Oscar and Riff have really great character arcs that continue into Godchild, and we do learn a bit more about Delilah members like Cassian, I found it hard to feel a ton of emotion for the romantic tragedies that are cited as fueling Cain in Godchild.

A fundamental aspect of Cain's character (and the series in general) is that he often doesn't realize how much he cares for someone until they're taken from him. Love being all the more meaningful after death is a mainstay of the Gothic genre, and we see this trope manifest in other characters throughout the series ("The Tragic Tale of Ms. Pudding" from The Sound of a Boy Hatching and "Mortician's Daughter" from Godchild Volume Three come to mind). It does help establish his personality, especially in Godchild; Suzette, his first cousin (and first love) being resurrected by his father's occult organization is a huge plot point close to the end of the series, playing with Cain's sense of longing for what is lost.

However, his pining for her falls a little flat upon seeing that their relationship is barely established in The Cain Saga, aside from a flashback to her death. The same happens with his fiancee Emeline, in that Cain spends almost the entirety of The Seal of the Red Ram Part One cheating on her, only to declare his love for her quite literally as soon as she dies. He then immediately falls in love with a resurrected corpse named Meridiana, rinse and repeat for The Seal of the Red Ram Part Two. It almost feels like whiplash.

In a sense, you could argue that Cain was an abused child who has grown into a traumatized young adult, and really only understands how to experience love through the lens of pain and tragedy. However, the way these relationships are written, with intense romances and deaths back-to-back, makes his emotions feel inauthentic and forced to the reader.

It's hard to find his melodrama believable when he talked about disliking her three pages before this.

2. Interspersing of random short stories

I suspect this was more the fault of Viz Media/Shojo Beat than the author herself, but it makes the story a little harder to follow. Kaori Yuki had previously written a few one-off short stories, and I guess Viz made the choice to add them in when publishing the Cain Saga. The short story "Ellie in Summer Clothes" appears at the end of Kafka, and most confusingly, the short story/novella "Double" was inserted right in the middle of Forgotten Juliet, breaking up Cain's story with an unrelated 1980's murder mystery before the final chapter.

Not only is it slightly jarring to go back and forth, it also doesn't make a ton of sense to me publishing-wise. These bound volumes were translated and released around 2006/2007, with the manga having been out in full since the late 1990's. There was no need to add filler while waiting for the next serial chapters to come out, so I'm confused as to why Viz made the choice to take up extra pages with unrelated shorts. I feel like they could have cut them for space and re-formatted the earlier chapters, so that both parts of The Seal of the Red Ram could be bound in one volume? I'm sure they had their reasons, but it makes for an odd reading experience.

3. The art and character designs

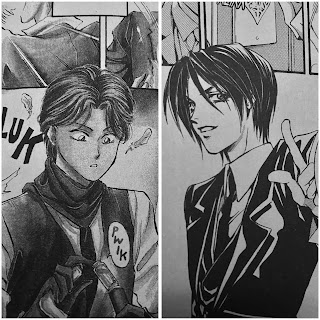

Godchild feels slightly more whimsical than The Cain Saga, I think in part due to the change in Yuki's art style. Godchild's art leans slightly cutesier and more exaggerated, where The Cain Saga still had the trappings of 1980's semi-realism. You can see this shift near the end chapters of The Seal of the Red Ram Part Two, but even that doesn't compare to Godchild Volume One. The men are leaner, lither bishounen caricatures of their earlier counterparts; Dr. Disraeli's hair constantly in motion, Cain's impossibly long limbs draped over couches and leaning on doorframes. The shading is darker, with more flat black coloring and a less liberal use of "sketchy" shading and grayscale.

Cain in Forgotten Juliet versus in Volume One of Godchild

Yuki writes in a few Godchild afterwords about being inspired by Gothic Lolita fashion and Japanese subcultural clothing brands like BATSU CLUB, and these influences shine throughout the series (notably on the splash pages). Mary Weather wears all sorts of ruffled dresses and flat rectangle headpieces reminiscent of early Innocent World (including the cutest Hospitality Doll-adjacent nurse outfit), while characters like Mikaila (Volume Four) and Marjorie (Volume Three) wear dresses that look heavily inspired by Atelier Boz. Mikaila even has a tiny Metamorphose/La Luice bunny pochette on her basket of venomous spiders!

La Luice's 2003 bunny pochette versus Mikaila's basket charm

In contrast, The Cain Saga looks a little less stylized and polished. The hairstyles and clothes lean more towards being period-accurate to the Victorian era, with a lot less pop cultural influence. The backgrounds and panels make more use of white space and hand-shading, and pages sometimes feel cramped or over-filled due to a lack of clean lines or black space. The Cain Saga seems inspired by the manga The Rose of Versailles, while Godchild feels more inspired by the band Versailles.

If you're a devoted Godchild fan, I don't think there's any downside to reading The Cain Saga. It isn't crucial to understanding the sequel series, but it's fun to see what started it all! Story-wise, it's also interesting to see how the Delilah organization starts, and the sacrifices (figurative and very, very literal) the members make in support of their cause.

I'm thinking I might do another post next week of the various EGL-adjacent outfits drawn in Godchild, and maybe a coordinate inspired by one of them! This is my first serious foray into blogging, so I'm eager to get some posts up and running.